I’ve been considering doing this blog for a while now. The intention of this blog entry is to describe the aerospace engineering degree and it’s effects on student’s from my own perspective. And how else would an engineer illustrate a concept, other than through a serious of graphs? I wouldn’t say it’s sugar coated, but when you think about it, do you really expect rocket science to be easy?

None of the graphs in this blog entry can be backed up by scientific evidence. I created each of them in MS Paint to reflect my own limited observations.

And what does chocolate cake have to do with any of this? Well, someone asked me if I liked my major. My initial reaction was “sometimes,” but then I really thought about it and tried to come up with an analogy that other people could understand-an analogy devoid of technical jargon. This is what I came up with:

Homework is like chocolate cake. I love chocolate cake, especially the super sweet milk chocolate with milk chocolate icing. Pure, simple, and exceptionally delicious chocolate cake. Even when I’m completely full, if you put a slice of chocolate cake down in front of me, I will eat it, and I will savor each and every bite. However, if you were to place a 5 layer, 12 inch diameter, chocolate cake in front of me and instruct me to eat it within an hour, that chocolate cake suddenly becomes daunting rather than mouthwatering. That’s how I feel about homework. More specifically engineering homework. I actually like solving the difficult problems that my professors assign me for practice, but when a combination of assignments accumulates into a daunting task, it reaches a point where it becomes too much. Often times engineering homework becomes too much of a good thing.

Only a true nerd could compare homework to chocolate cake.

With that, I will begin delving into my own personal analysis of the engineering curriculum, with handy-dandy graphs to illustrate my theories.

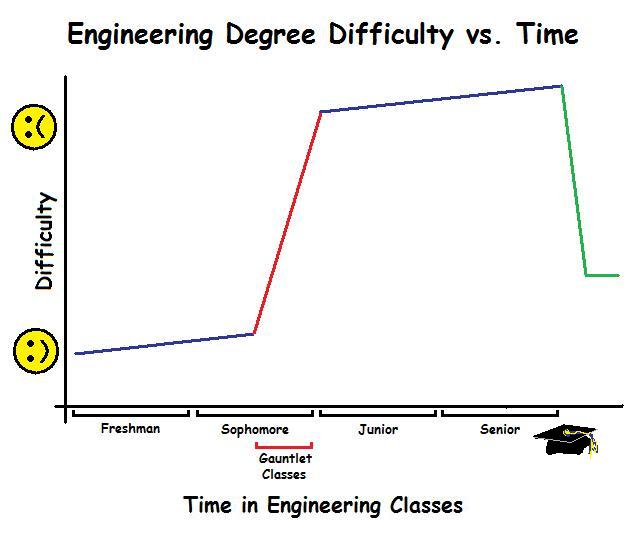

As you can see in the graph above, the difficulty of your classes increases dramatically over time. One might ask what these mysterious Gauntlet Classes are. Well, the typical engineering student encounters a semester of classes which many engineering students refer to as “The Gauntlet.” These classes may include a combination of the following: Solid Mechanics, Fluid Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aerodynamics 1. Some students can decrease the slope of the difficulty increase by splitting “The Gauntlet” up over semesters, but inevitably, after completing “The Gauntlet,” the level of difficulty in engineering classes remains rather constant.

As you can see in the graph above, the difficulty of your classes increases dramatically over time. One might ask what these mysterious Gauntlet Classes are. Well, the typical engineering student encounters a semester of classes which many engineering students refer to as “The Gauntlet.” These classes may include a combination of the following: Solid Mechanics, Fluid Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aerodynamics 1. Some students can decrease the slope of the difficulty increase by splitting “The Gauntlet” up over semesters, but inevitably, after completing “The Gauntlet,” the level of difficulty in engineering classes remains rather constant.

Engineering classes start off relatively easy with the basics such as math, physics and humanities requirements. For me, a veteran of an intense magnet program and multiple AP classes in high school, freshman year was actually easier than what I had experienced during my Junior and Senior year of high school. It wasn’t at all what I expected. I wasn’t really complaining, but I was a little surprised because I had expected college to be a lot harder, and it kind of lured me into a false sense of security.

Then, because of all of my AP credits, I took “The Gauntlet” at the beginning of my sophomore year, minus Aero 1, which I am taking now. It was as though the engineering program was laughing at me and cackling “Ha! Tricked you! You thought it was going to be easy, huh? Well, here is the real stuff! Welcome to engineering!” The jump in difficulty that I experienced during the first semester of my sophomore year was what I had originally expected from engineering, just about a year delayed.

“The Gauntlet” is by no means impossible, but it will likely be the most difficult semester you will ever encounter in engineering, mostly because you have to get used to the sudden difficulty and time devotion increase. After “The Gauntlet,” classes remain difficult, but you aren’t going through that transition period any more. You get used to it, and you adapt to accommodate the changes.

For the most part, the engineering faculty and academic advisers are well aware of the challenges and adjustments required to make it through “The Gauntlet” and they will do the best to help you succeed.

In my own personal experience from what I have seen of the engineering world outside of school, after graduation your work load and difficulty decrease significantly. A career in engineering is by no means easy, but it is not nearly as difficult as being a student who spends about 16 weeks on in an intense load of courses and homework consisting of 4-6 different topics before switching to a new set of 4-6 topics with an entirely different set of professors who have different expectations and styles that you have to get used to all over again. Then there is simply the shear load of homework.

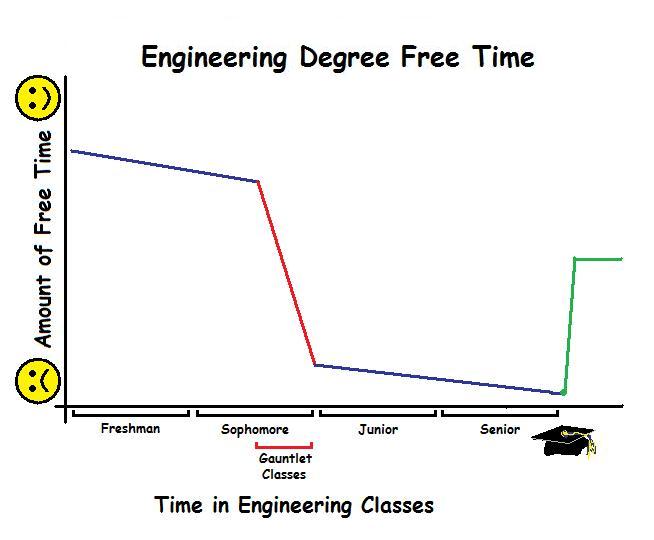

Many engineering students spend the majority of their evenings and weekends doing homework. When they become full time engineers, they usually get their nights and weekends back. For about the first month of my co-op, I had no idea what to do with all the extra time, but I quickly found activities to fill them.

Final Exams are just about the most stressful and challenging academic weeks for both students and professors. During one week you will be required to present your understanding of all of the new subjects that you have learned about during the previous 15 weeks, in a format that pleases that particular professor the most.

You will have many performance evaluations and presentations during your engineering career to stress about but in my very limited experience, they are no where near as stressful as final exams. As far as performance evaluations go, if you are anything like me, and simply can’t give less than your best on a day to day basis, your supervisor will notice that, and you don’t need to worry about performance evaluations. As far as presentations go, usually you will create your own presentation and it will be on a topic that you are very comfortable with. The presentations are done on your terms, which makes them much less stressful than final exams, where you are often guessing what you think your professor thinks is most important.

From what I have seen in the engineering world, you work on a specific set of projects in a certain direction for an extended period of time. You have only a few supervisors to get used to and you don’t usually have to get used to a new set of leadership every 16 weeks. It will differ from job to job, and if you are working on a high profile, priority project with quick deadlines, your work could be much more difficult than what I have generalized.

As you can see in the graph above, the amount of free time that an engineering student has as they progress in their degree decreases dramatically over time. When comparing this graph to the first graph, Engineering Degree Difficulty vs. Time, the correlation is unmistakable. Of course if the only thing that you do is school, and you don’t join in extracurricular activities (which isn’t as uncommon as you might think for super nerdy, socially inept engineers), you will have more free time than is represented in the graph above.

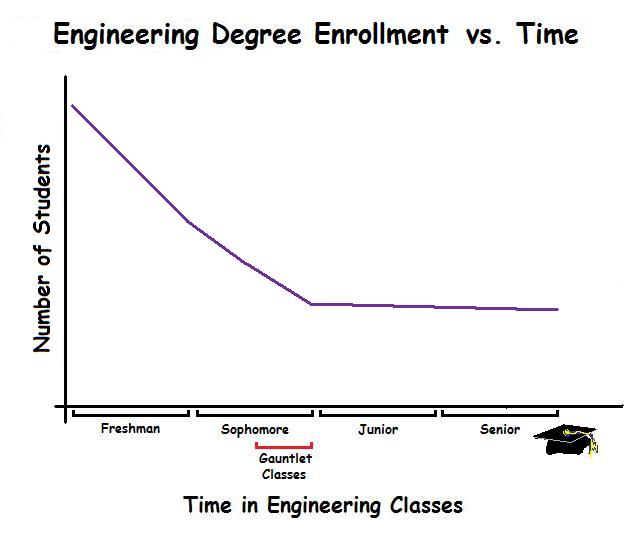

The biggest drop in enrollment in the engineering degree program that I have observed has been freshman year, when the first round of students realize, “Hey, I was confused, I don’t really want to do this. It wasn’t what I thought it would be.” Then the rate decreases until the end of “The Gauntlet.” If an engineer makes it though “The Gauntlet,” they are usually committed to sticking out the rest of the degree.

The biggest drop in enrollment in the engineering degree program that I have observed has been freshman year, when the first round of students realize, “Hey, I was confused, I don’t really want to do this. It wasn’t what I thought it would be.” Then the rate decreases until the end of “The Gauntlet.” If an engineer makes it though “The Gauntlet,” they are usually committed to sticking out the rest of the degree.

During orientation at many large universities, a representative from the college of engineering will tell the engineering freshman to look to their left and then their right before announcing that two out of every three students will not graduate from the engineering program. Although this drop out is not nearly as dramatic at Riddle, many of the students who initially begin engineering do not complete it.

I believe that the drop rate is lower than the traditional rate because a student doesn’t usually come to Embry-Riddle unless they are exceptionally passionate about aerospace, and usually that passion can help a person get through the most difficult of challenges.

Why do people drop engineering? Well, primarily for the reasons in the first two graphs. They can see how difficult the path is before them and they decide that they want to go a different route. Others realize that they don’t like math and physics as much as they thought when confronted with a full schedule of math and science classes. I don’t really know all the reasons, but those are the two most common reasons I hear.

What happens to the drop outs? Well, some of them go home. They attend community college to find out what they really want to do, or go straight to another university if they already know what their new passion is. Some students, who have already established themselves at Embry-Riddle and do not wish to switch universities, switch to less challenging majors such as Global Security and Intelligence Studies, or Aviation Business, or Aeronautical Science. None of these majors are easy, but as the engineers like to say, “they aren’t exactly rocket science,” and if they still have a passion for aerospace, though not necessarily for engineering, it allows them to pursue their passions from a different direction.

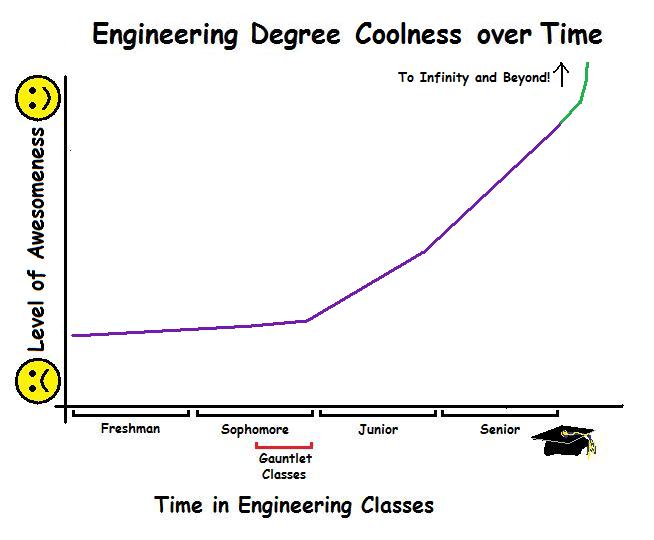

After your sophomore year, your general engineering classes are pretty much done, and you begin to get into engineering courses for your specific engineering degree, which should increase in interest and complexity. During my last space mechanics class we analyzed how the trajectories of the lunar landing missions of the late 60s and early 70s were designed. How cool is that? Classes only become more interesting as you reach your senior year and you combine all of the concepts that you have learned into two courses that simulate a complete aircraft or spacecraft mission in the case of aeronautics and astronautics, respectively.

When I was at NASA, a fellow engineer reminded me that for aerospace engineers “the sky is not the limit,” a play on the phrase “the sky’s the limit.” The kind of projects that you will work on as an engineer are pretty much epic in their level of awesomeness. You could design a cutting edge, primarily composite commercial aircraft, or work on the spacecraft or station that will make human habitation on the moon possible. Whatever you work on, you will realize that all of the hard work that you put in during college was well worth it.