by MaeLee DeVries

My name is MaeLee DeVries and I am a senior at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (ERAU) in Prescott, Arizona. I am majoring in Forensic Biology and I am interested in trace evidence, which is why I chose the research topic of trace evidence of makeup. We’ve all seen it on crime shows, there’s a piece of evidence that could not have been found, but somehow the investigators are always able to trace it back to the perpetrator in the end. While that is not wholly reality, it is not completely far from the truth either. Trace evidence can be very difficult to deal with because it is difficult to see, difficult to handle, and even more difficult to avoid cross contamination. However, if done properly, the analysis performed on trace evidence can corroborate stories and determine the truth. This is why I wanted to do this research because the more data there is, the stronger statistical values can be, which can create more conclusive evidence. Hopefully, this research helps contribute to a usable and searchable database for makeup to help investigators speed up investigation processes and be more objective in their investigations. After all, objectivity is one of the main goals of evidence-based research because it excludes bias and seeks the truth.

To be able to do this research, I had the privilege of receiving a Space Grant and being selected to be funded for an Ignite Undergraduate Research Project during the fall semester of 2020. The goal of this research was to support and develop a method for easily distinguishing the morphological and chemical features of various lipsticks and eyeshadow palette samples. There is a lot of data that still needs to be collected in trace evidence analysis of makeup research to fill the gap of information that exists; therefore, this research will demonstrate nondestructive analysis techniques that can help trace the evidence back to its source by providing more data that can be utilized in crime laboratories to assist in solving crimes. As the project leader and the only student on this project, my duties were to prepare the research samples, analyze the samples using a light microscope, Fourier-Transform Electron Microscopy (FTIR), and learn how to use the Scanning Electron Microscope in tandem with an Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (SEM/EDS) to analyze the potentially toxic chemicals within and individualistic characteristics of the different brands of makeup samples

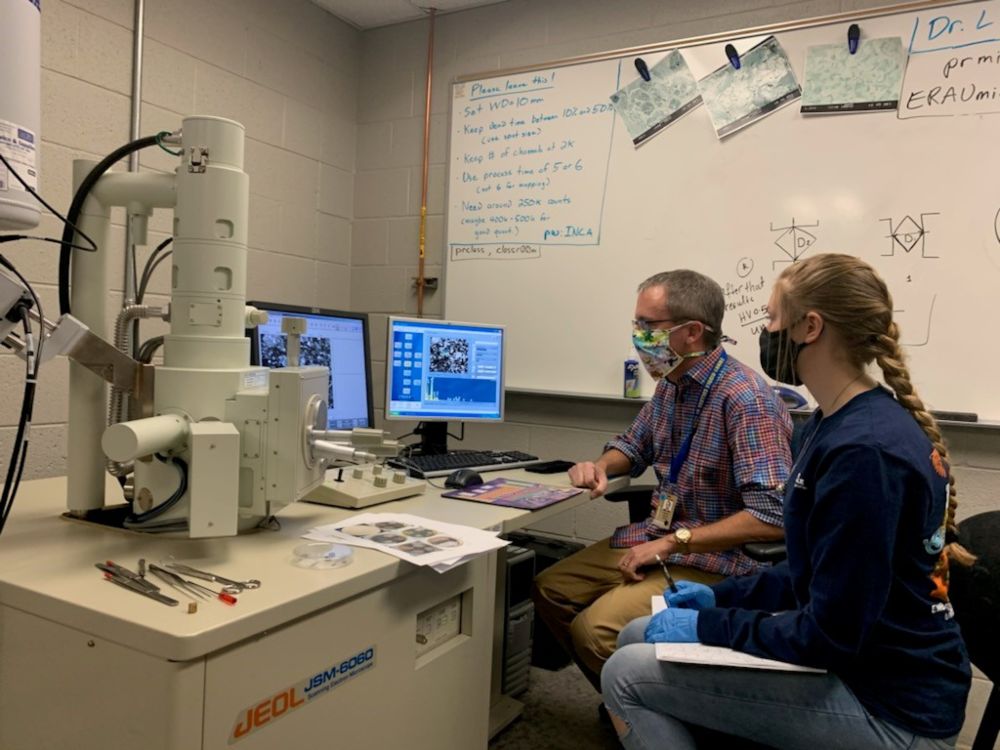

In this research my mentor, Dr. Teresa Eaton and I studied three different brands of eyeshadow and two different brands of lipstick. Originally, we were going to study six different brands of eyeshadow palettes; however, due to this being my last semester, time constraints did not allow me to study all of the samples I would have liked to; therefore, we studied palettes from Maybelline, Revlon, and Milani and a red lipstick sample and a pink lipstick sample each from Milani, and Wet n Wild. I did, however, run into some hiccups along the way, which is nothing new if you are familiar with research. First, preparing the samples took much longer than expected due to the meticulous cleaning and recleaning of materials to avoid cross contamination. When dealing with evidence, this is paramount. The second problem I ran into had to do with the SEM/EDS. While I was in the middle of viewing and analyzing my samples, the filament on the SEM/EDS burned out, putting my entire project to a halt. The filament allows for the visualization of the samples because that is where the electron beam originates, which without, the visualization is not possible. Obviously, I cannot research blindly; however, the kind Dr. Lanning (pictured above) came to my rescue, replacing the filament within hours. These roadblocks were impeding, but I got past them and was able to complete what I could of my research.

I analyzed a total of 37 samples viewed under the light microscope and analyzed using FTIR and 41 on the SEM/EDS, so a lot of samples were run, just not all of the samples I wanted to analyze. The techniques used were not invasive, other than the SEM/EDS and were able to discriminate between palettes, but not individual samples. FTIR was not invasive and quick, but only showed a fingerprint, while SEM/EDS was destructive, but showed the chemical composition and only used a very small amount of sample.

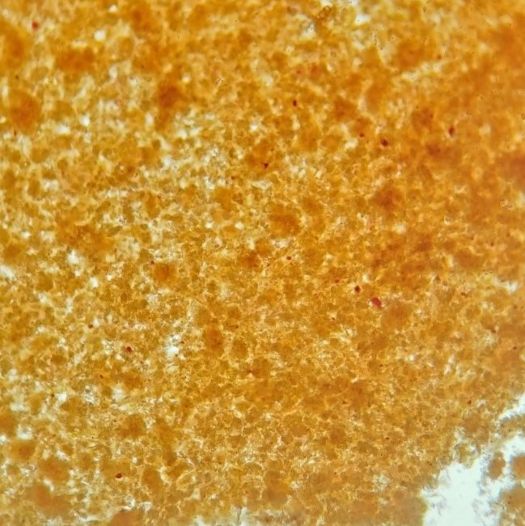

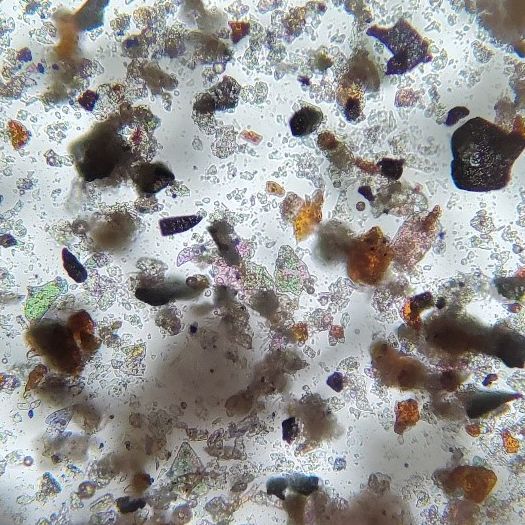

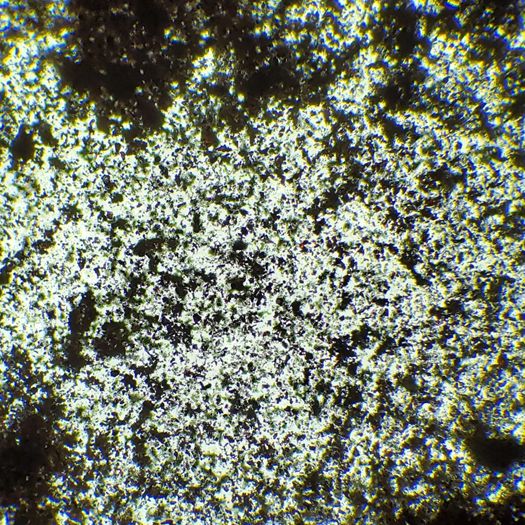

Optical Microscopy Images

Figure 1. Milani eyeshadow

Figure 2. Maybelline eyeshadow

Figure 3. Revlon eyeshadow

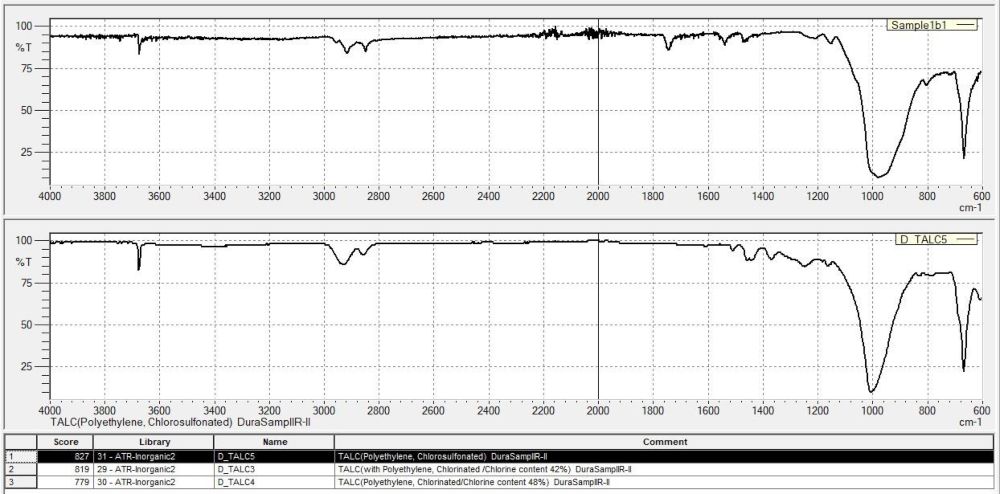

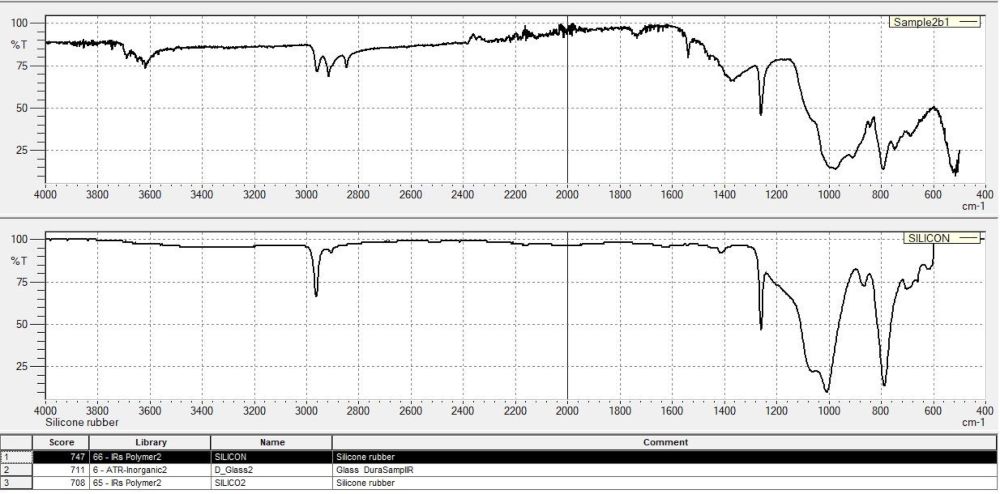

FTIR Spectra and Data

As you can see, Figure 1, 2, and 3 demonstrate the light microscopic view of a Milani eyeshadow sample, a Maybelline eyeshadow sample, and a Revlon eyeshadow sample, respectively. In my observations, I noted signature red-pink circular particles in nearly all of the Milani eyeshadow colors, which can help distinguish the samples from other palettes. In the Maybelline reflective eyeshadow sample glass-like and other reflective and metallic-like particles were noted, which were consistent with most of the shiny and glimmering samples. The Revlon eyeshadow was fine and fibrous, which was common throughout the more neutral and less glittery and shiny eyeshadows.

Graphs 1 and 2 are both FTIR spectra and show that there is a broad band at around 1000 in both sub-samples 1b and 2b. This was the same amongst nearly all of them, but other peaks helped differentiate between palettes based on what the chemical fingerprint was most likely related to. Most of the sub-samples from Sample 1 (Maybelline) were related to TALC, most of the sub-samples from Sample 2 (Revlon) were related to silicon, and most of the sub-samples from Sample 4 (Milani) were related to paraffin. This simple information is significant due to the differentiation it provides between palettes.

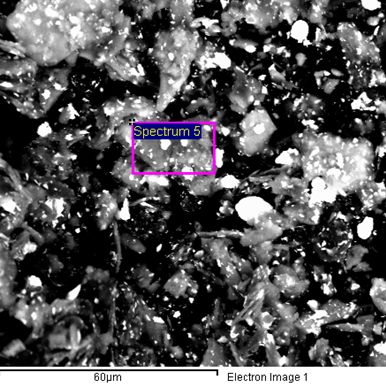

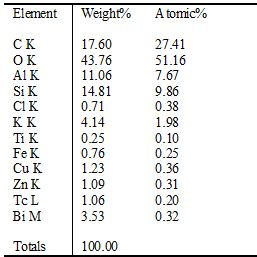

SEM/EDS Images and Data

Figure 4. Revlon eyeshadow

Figure 4 shows the SEM image of eyeshadow sub-sample 2a by Revlon. The elemental composition is shown to the right demonstrating that there are two heavy metals that were not expected to be within this sample, Tc and Bi. Both are not toxic at low levels.

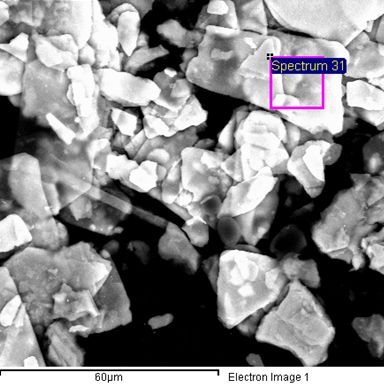

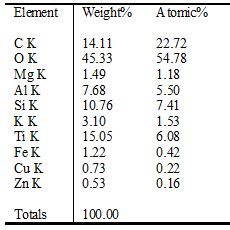

Figure 5. Maybelline eyeshadow

Figure 5 shows the SEM image of eyeshadow sub-sample 1i by Maybelline, which demonstrates expected heavy metals such as Fe, Cu, and Zn.

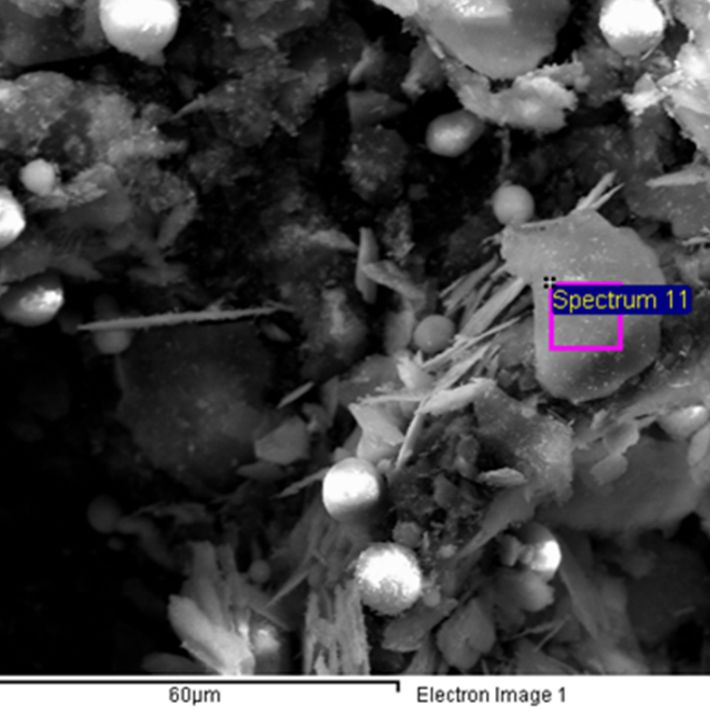

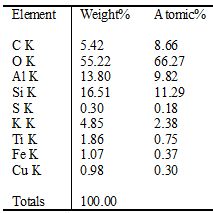

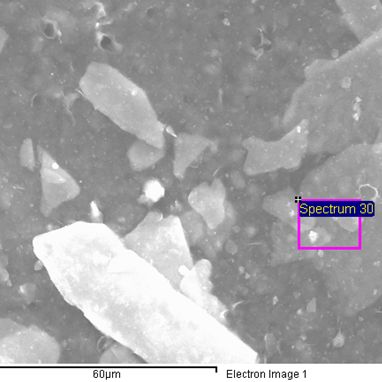

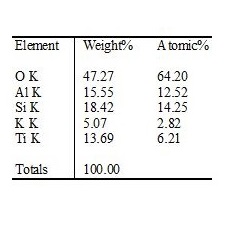

Figure 6. Milani eyeshadow

Figure 6 shows the SEM image of eyeshadow sub-sample 4e by Milani. Again, expected heavy metal content is observed as well as cylinders of carbon suspected to be some form of microplastics.

Figure 7. Wet n Wild lipstick

Figure 7 shows the SEM image of lipstick sample 16 by Wet n wild. Expected chemical composition is seen.

Finally, Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7 show the images from the SEM and the chemical composition from the EDS for eyeshadow and lipstick samples. Figure 6 shows that there are some heavier more toxic chemicals in the sample compared to the other samples, but these chemicals are not toxic to humans at very low quantities. There were no distinct chemical differences between the palettes other than Sample 2, which had Technetium and/or Bismuth in several of the samples. The SEM images were quite fascinating to look at, and while each sample did look different in its own way, it would be a subjective way to look at evidence and as I said earlier, that is not the goal of trace evidence.

My final results for this research project indicated that the chemical analysis techniques, FTIR and EDS, can potentially differentiate between palettes, but not individual sub-samples, while the optical microscopy techniques, light microscopy, and SEM, may be useful in differentiating between sub-samples in color and morphology. However, as I mentioned above, this process is much more subjective, and it is important to have objective methods of analysis in trace evidence. This analysis is not discriminatory enough by itself to differentiate between individual sub-samples, though it may be useful for differentiating between palettes. In the end, there was ample data gathered that demonstrated elemental, morphological, and spectroscopic properties of the samples for results and future analyses.

In conclusion, I hope this is not the end of this research because there is so much potential that this type of research has to assist crime laboratories in reaching the truth faster and more objectively. The opportunity I have had with this research project has yielded great experience and understanding for me in the future. Personally, I want to be a forensic DNA analyst, which must be an objective analysis technique, because the main goal is providing the truth. Not who we think did it. DNA analysis uses databases, which are crucial to conclusions; however, DNA cannot act alone in submission of evidence. Stories and other trace evidence must align in order for the truth to be found; therefore, other forms of trace evidence are vital and necessary. I love science and the potential it holds. After all, it is prepared to provide the truth, if we handle and analyze it properly.